Ben Thomas

September 12, 2024Share

David Seymour, along with the other coalition party leaders, is welcomed on to the marae at Waitangi in February. Ben Thomas wonders whether the wording of ACT’s Treaty Principles Bill will deliver rather more than Seymour and his party intended.

LAWRENCE SMITH

Ben Thomas is a regular opinion contributor. He is a public relations consultant and political commentator who has worked for the National Party.

OPINION: Has David Seymour had a Road to Ngāruawahia conversion?

In January, the late Kiingi Tūheitia rebuked the ACT leader’s controversial proposed bill to hold a referendum on rewriting the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi developed by the courts, government and the Waitangi Tribunal.

“There’s no principles, the Treaty is written,” Tūheitia said. “That’s it.”

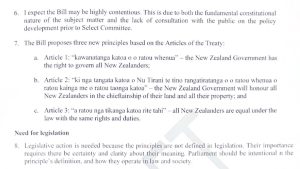

Seymour was one of the thousands of mourners and dignitaries who paid respect to Tūheitia at his funeral tangi at Turangawaewae marae last week. Back in Wellington, he had Cabinet sign off drafting instructions for the bill, with some striking changes to the planned replacement principles.

Rather than making the bill more moderate, in the face of vociferous criticism, it is instead potentially more radical than those critics and even Tūheitia himself could have hoped for in their wildest dreams.

In particular, it appears that it may effectively incorporate the Treaty itself into law, a legal first that even the most activist judges have balked at.

The text Cabinet has agreed on states that one of the principles, corresponding to Article Two of the Treaty, would read that: “The Crown recognises the rights that hapū and iwi had when they signed the Treaty. The Crown will respect and protect those rights.”

It goes on to say that those rights and interests differ from rights of other New Zealanders only when recognised in legislation. Legislation like, for example, a Treaty principles law.

This is potentially a far, far more progressive position than the current Treaty principles allow for.

Play Video

3:04

Seymour’s Treaty bill will get the full 6 months at Select Committee

The current Treaty principles are less an interpretation of the Treaty (or te Tiriti, the Māori text) and more of a creative exercise in compromise, heavily weighted in favour of the results of the imperfect evolution of modern New Zealand society and the inescapable political reality of the Crown’s sovereignty.

Principles such as a situationally dependent notion of partnership, and a “duty of active protection” of Māori interests, recognise the political reality, while acknowledging the rangatiratanga of iwi and hapū should at least be considered when decisions are made affecting those interests set out in the Treaty.

They are basically principles to guide the Crown’s thinking in how it should make space to allow for the exercise of traditional self-determination and authority, including input into decision-making, in a way that doesn’t significantly disrupt the massive redistribution of Māori property into both private and public hands since 1840.

Obviously, these principles grant fewer rights than the Treaty itself, which guaranteed at least “undisturbed possession of their properties, including their lands, forests, and fisheries, for as long as they wished to retain them”, and at a maximum something like self government.

The original intent of ACT’s policy was to replace these principles with broad statements about the rule of law, the recognition of property rights, and equal rights for all citizens.

The effect of enacting these inoffensive-enough provisions by pasting them over the top of the existing Treaty principles, however, would be to restate the articles of the Treaty but without reference to Māori.

“Treaty principles law without the Treaty” was presumably a bridge too far to defend historically and intellectually. In contrast, the new principles appear more like“Treaty in law, without the principles”.

Under Cabinet’s decisions, the law will not alter or amend the Treaty itself, and it would require the Crown to respect and protect the rights outlined in the Treaty as they were in 1840, not just a few paltry rights to consultation and decision input.

One of various protests seen around the country in the past year against coalition policies seen as hostile to Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

BRADEN FASTIER / STUFF / BRADEN FASTIER

This would be a requirement in the interpretation of any legislation where the Treaty principles were relevant (according to the courts, and officials’ advice on New Zealand First’s own Treaty clause review policy, this is all of them, not just those with dedicated clauses).

Reading the accompanying Cabinet paper, it’s clear enough that this radical position is not what ACT is trying to achieve, which is to narrow the rights of iwi and hapū, not expand them. It’s not clear how the proposal ended up as it has: perhaps another miracle on the road to Huntly, transformation.

Officials are either playing along or have simply analysed Seymour’s intention, rather than the proposed words that present a Maui-sized fish-hook to catch onto judicial interpretation not seen since section 9 of the State Owned Enterprises Act hauled up the beginnings of modern Treaty settlement process.

Maybe it doesn’t matter in the end. Seymour has managed to secure a full six month select committee process to attract maximum din and rancour from motivated and moneyed activist groups, who will likely not concern themselves with the textual details.

That will help ACT appeal to a base of voters not impressed by its much more worthy and substantive achievements such as the Ministry of Regulation and record Pharmac funding.

But National and New Zealand First remain clear they will not support it through a second reading in any form. Conversion or no, the bill is still dead as soon as it hits the air.