( By Te Maire Tau )

The Song of Waitaha begins with adedication and ends witha “patriarchal blessing” from Pani Manawatu, past Upoko Runanga of the Ngai Tuahuriri hapu. A good start. One would expect then that the traditions that this elder learnt would be evident in the book. That the traditions of his wife Hutika Pitama, and his family(Solomon) would be liberally sprinkled throughout.

Those traditions do not make it into this book. How does the writer know this?

The writer, mokopuna to Pani Manawatu and one who spent his childhood and early adult years with this elder,was given his manuscripts after hedied. Those manuscripts arepart of what is known as the “Pitamascripts”.

It is those manuscripts that hold the raditions and histories of Pani Manawatu’s elders, along with the countless manuscripts produced last century and early this century by Taaree Maiharoa, Wikitoria Paipeta, Hoani Maaka, Taare Tikao, Hariata Beaton, Ware Rehu and Rawiri TeMamaru.

Pani Manawatu was the writer’s Poua. lndeed I do not see how Pani Manawatu would have approved of this book as he died before it was published and before the traditions were prepared. Who is responsible forSong of Waitaha?

The book is not clear about who the author is, although the publicity launch of this book would suggest that Barry Brailsford is the principal writer and thein for mantis Peter Ruka. What qualifies either of these people to write about the Waitaha?

Certainly not whakapapa. Neither are able to claim descent from Rakaihautu, Hotu Mamoe or Tahu Potiki the principle ancestors of the South Island Maori now known as NgaiTahu. Brailsford has had a long association with Ngai Tahu. His book The Tattooed Landthat deals with the history of the South Island Maori was a best seller as was his follow up Greenstone Trails.

Ruka’s background is more vague

Ruka claimed Ngai Tahu descent, yet has never enrolled as a Ngai Tahu beneficiary. This is not unusual. Many Ngai Tahu do not enrol. Yet Ngai Tahu from the home marae generally know what house of whakapapa tribal members slot into. The Ngai Tahu Trust Board whakapapa expert, Terry Ryan is not aware of Ruka’s Ngai Tahu affiliation.

This is unusual as Ryan knows the whakapapa of Ngai Tahu intimately. What we know isthat Ruka has no connection to any Ngai Tahu runanga or marae. The Waihao and Moeraki Runanga, cradles of Ngai Tahu whakapapa, do not recognise Ruka as one of theirs. Ruka came to prominence within Ngai Tahu in 1986 when he approached Rakihia Tau, then secretary of the Ngai Tuahuriri Runanga, to help in the formation of fishing evidence for the Waitangi Tribunal. It soon became apparent that the evidence presented was not traditional.

That suspicion was confirmed by the tribunal who would not consider Ruka’s evidence. The tribunal agreed with Ngai Tahu that the evidence was taken from a text book on fishing rather than anunnamed kaumatua informant as Ruka had said. Ruka’s evidence did not stand examination when compared to traditional fishing information from Ngai Tah u-Waitaha-Mamoe fishermen.

(David Graham,A treasury of New Zealand Fishers p48 Ngai Tahu Sea Fisheries Report, Ngai Tahu, 1992.)

In theory this should have been the end of Ruka’s involvement with Ngai Tahu and South Island Maori history. However by 1988 Rakihia Tau had proposed to Michael Bassett, the Minister of Internal Affairs, that Ruka and Brailsford write a book on Rapuwai, Ngai Tahu, Ngati Mamoe and Waitaha histories. The project was called Nga Tapuwae 0 Te Waipounamu or Footsteps and was launched during the inglorious year 1990 by the 1990 Commission. It is important to realise that at this stage the Footsteps Project was to include the history of Ngai Tahu and Ngati Mamoe. There was also an assurance that Brailsford would work under the cloak of the Ngai Tuahuriri Runanga

as well as other local Ngai Tahu runanga.

Furthermore the Kaiapoi Pa Trustees were to monitor the overall text. Ruka and Brailsford were to be accountable to the Kaiapoi Pa

trustees. The Kaiapoi trustees are Ngai Tahu, but also claim Waitaha descent lines. One of the trustees Mr John Rehu, comes from a long line of respected tohunga from both Ngai Tahu and Waitaha. Tau’s selection of Ruka and Brailsford was to prove unfortunate. Brailsford, a Pakeha historian who was never given access to tribal manuscripts by his “Upoko” Pani Manawatu orthe Pitamawhanau, and

Ruka who’s evidence was, as one scholar noted “wildly improbable”, was a combination waiting to explode

into realms of fantasy. (Atholl Anderson, p48 Ngai Tahu Sea Fisheries Report, Ngai Tahu 1992.)

By 9 April 1989 Tau was critical of Brailsford’s delVing into spiritual matters belonging to Maori. On the wider Ngai Tahu front others were unhappy with Ruka’s involvement. The same anger was not directed to Brailsford for whom many Ngai Tahu still had high regard. Elenor Murphy of the Otakou Runanga wrote to the 1990 Commission requesting that the “Footsteps Project” be reappraised. Tau wrote to staff of the Commission “I support the editing of the written word”. Tau’s attitude to this was summarised in a note “Proof first,

gives credibility…”.

As a result of the 1990 Commission’s uneasiness, the Footsteps Project was suspended until Ngai Tahu had resolved the problem on 1 July 1989. A meeting was quickly convened where Ngai Tahu meet with Peter Ruka.

The outcome was that Ruka was to supply his whakapapa of his descent from Ngai Tahu or the tribe would withdraw support for the project. The whakapapa was not forthcoming and Ngai Tahu kaumatua Tipene O’Regan, Waha Stirling and Rakihia Tau informed Barry Brailsford of Ngai Tahu’s withdrawal of support for the project

By this stage Rakihia Tau was deputy Upoko Runanga and acting Upoko for his uncle Pani Manawatu, who was slowly dying of cancer. Both Tau and Pani Manawatu were concerned at Brailsford and Ruka’s apparent disregard of their accountability to the Runanga and Kaiapoi PaTrustees. Pani Manawatu was to pass away in 1991.

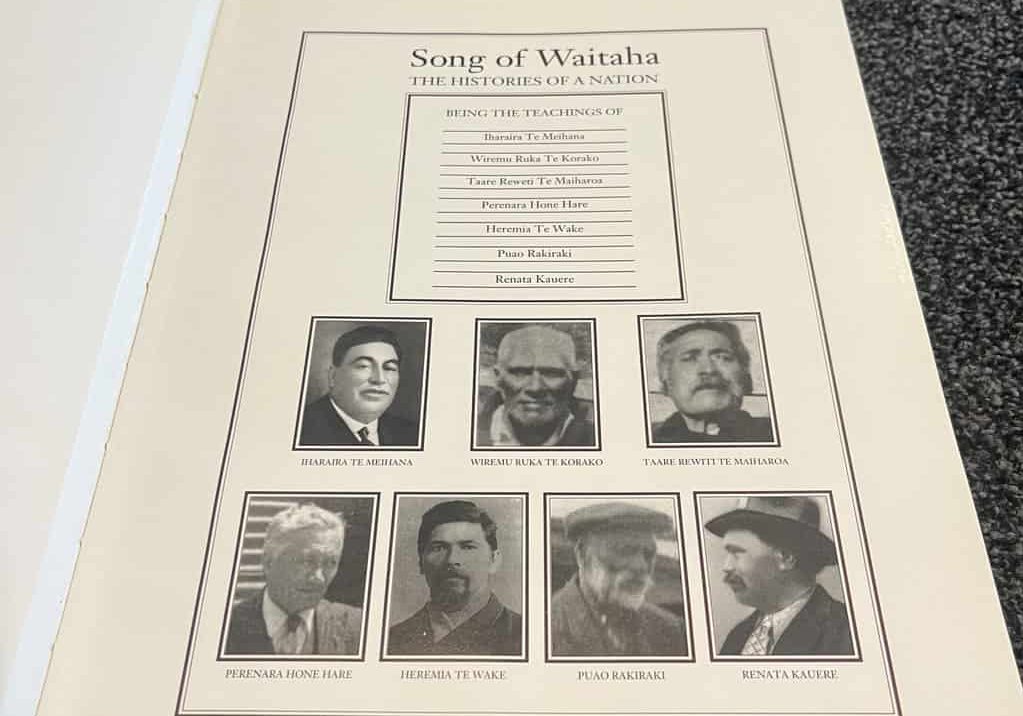

It was at this stage that the book became “Waitaha” in its direction. In doing this the books direction could then be focused on the South Island but the histories did not have to be Ngai Tahu. The result is the publication of Song of Waitaha. Although not stated, but certainly suggested, is that the information stems from Te Maiharoa and Puao Rakiraki.

This isinteresting, the writer owns and has seen extensive whakapapa texts from Te Maiharoa’s descendants and his students Wi Pokuku, Hoani Kaahu and Herewini Ira. None of their whakapapa texts support the traditions of Song of Waitaha. Ironically the book

says, “until now we have said nothing, when others wrote our histories for us and brought error to the paths of truth”.

The problem for Brailsford and Ruka is that while Te Maiharoa did not write his histories, his whanau did, particularly his mokopuna Wikitoria and his student Wi Pokuku.

Those stories told by Wikitoria Paipeta, Herewini Ira, Hoani Kaahu, Wi Pokuku and even Taare Te Maiharoa are significant in that they

are consistent with one another. Much of their information was captured by Herries Beattie who published extensively on Ngai Tahu,

Ngati Mamoe andWaitaha traditions. Maori who learnt from these elders were Hoani Maaka, Henare Te Maire and latterly Te Aritaua Pitama, second cousin and close friend to Pani Manawatu.

None of these people instructed Brailsford or Ruka. How could they? Brailsford is Pakeha and cannot claim aitaha whakapapa nor did he meet or learn from the kaumatua give above.

Likewise, although Ruka is Maori, he has yet to give his whakapapa to Ngai Tahu let alone Waitaha. There is general belief that Ruka is

a mixture of Nga Puhi and Ngati Whatua as his parents were from Whangarei and part of the religious sect called Rapana.

Like Brailsford, Ruka did not sit with any of the kaumatua. A solid critique of the book would be time consuming. One feels as if one is reading the saga of the smurfs and their migration to the land of the hobbits.

The writer could find little that could qualify as authentic tradition. Basic placenames are replaced. We are told that the South Island was called “Aotearoa” and the North Island “Whai repo”. Mythicalraces such as the Ure Kehu come to life and

a suspiciously new race called Maoriori is brought to our attention.

The very real danger is that this book may be seen by Pakeha, and Maori not raised by the kaumatua, as traditional material. From an

historians point of view there is lack of scholarship due to lack of references.

We are asked to believe in traditions without being told the identity of the informants or being shown evidence that the traditions have

survived intact. Brailsford admitted in an interview with the magazine New Spirit that at times he became lost when writing this book.

I suspect the book tells us more about Brailsford’s search for his identity or perhaps his loss. Michael King wrote in Pakeha: I feel nothing but sadnessfor Pakeha who want to be Maori, who believe they have become Maori usually empty vessels waiting to be filled by the nearest exotic cultural fountain who romanticise Maori life and want to bask forever in an aura of aroha and awhina.

These are the same people who crumple with disbelief and shock the first time somebody calls them honky or displays the more robust characteristics of Maori behaviour. No doubt Brailsford was crushed when Ngai Tahu-Waitaha kaumatua such as Pani Manawatu and Rick Tau withdrew their support from the Footsteps Project.

The tradgedy is that Brailsford looked for another “exotic fountain”.

SOURCE: https://ngaitahu.iwi.nz/assets/Documents/TeKaraka02.pdf